By Scott Minto

A couple of years before the 2014 referendum, the Economist published an article called “Skintland’, accompanied by a sneering, condescending front cover. The feature it purportedly advertised was a hatchet job on Scotland, which cobbled together some fairly bog-standard Unionist innuendo, supposition and misrepresentation amounting to nothing much that we haven’t heard a hundred times before.

The most interesting thing about the article was that it started with a preamble about the Darien Scheme, a 17th-century business venture which went horribly wrong and which Unionists are very fond of bringing up as a stick to beat Scottish nationalists.

Here, we’re going to look at the theme of BritNat mythology, and in particular the re-writing of the story of the Darien Scheme to that end. Trust me, it’ll be fun.

First though, a report, written by Professor Malcolm Chalmers about the defence of an independent Scotland, but which, for some reason, started with Darien. He wrote:

“The failure of Scotland’s fleet to establish a colony in Central America in 1698-99 (the ‘Darien adventure’) was a key part of the chain of events that led to the Act of Union in 1707. For it convinced the business classes that they needed the military protection of the Royal Navy if they were to benefit from the new riches that colonialism promised. They were right. Scotland’s economy was transformed in the two centuries that followed, in large part because of the access to export markets made possible by the Union.”

But this account is a somewhat airbrushed one. The story of Darien is a tale of betrayal, power, and military and political might brought to bear against Scotland. Professor Chalmers is right in one regard however – it was indeed the Treaty of Union that gave us access to Commonwealth markets, and it was the Commonwealth (rather than the Union per se) that provided the opportunities for Scots. These opportunities were previously denied to Scotland, and amounted to far more than mere trade. Their opening swiftly led to the development of a large Scottish diaspora throughout the world, but most noticeably in Commonwealth countries and the United States.

Darien was a disaster, of that there can be no doubt, but it wasn’t the end result of any inherent flaw in the Scottish psyche, or an indicator of the inability to manage our own affairs. That’s just the position the BritNat mythology wants to portray.

So what IS the story of Darien? To find out, we first need to rewind a little further. And go and grab a coffee or a cup of tea – you might need it.

The relationship between Scotland and England in the 14th and 15th centuries was tempestuous at times, with one of the last major flare-ups arising in 1489 when Sir Andrew Wood was forced to clear the Scottish seas of English privateers, capturing five and bringing them as prizes into Leith. Aggrieved by this success, Henry VII of England fitted out three privateers in 1490 to exact vengeance, but after an extended battle ranging from the Forth to the Tay, Henry’s ships were all captured by Wood.

After that skirmish things remained relatively uneventful until the Union of the Crowns in 1603, with Scotland thereafter finding itself England’s ally and friend. Yet after the Union of the Crowns Scotland became progressively poorer, neglected by its King in London and dragged unwillingly into England’s wars.

In the 1620s, Scotland fought naval wars as England’s ally, first against Spain and then against France (despite the Auld Alliance), but refused to send conscripts to the Royal Navy, claiming that Scotland had no deep-water sailors. This was a bending of the truth on Scotland’s part, as several squadrons of Scottish warships (known as the “marque fleets”) put to sea, supported by individual privateers licensed with letters of marque and three sizeable ships of the Royal Scots Navy.

But Scotland didn’t want to send these resources away, as their intended role was defensive protection of the east coast trade routes, which led to them being mainly privately funded. Scotland’s naval priorities were the protection of national trade, and the pursuit of profitable raiding cruises against enemy cargos. They lacked the large, purpose-built warships of the Royal Navy, and didn’t share the English policy of building a heavily-armed royal fleet to project military power against foreign enemies.

Despite these efforts, Scotland quickly found itself drawn into the war, proving to be a very capable ally. The “marque fleets” replaced the Royal Navy as the patrol squadrons in the Irish Sea, and subsequently joined the private navy of the Lord Lieutenant of Nova Scotia in a force that for a short while made Scotland the dominant imperial power in Canada.

In 1632 Scotland lost Nova Scotia – her only colony – as a result of the English war against France. England’s Dutch wars subsequently compromised valuable trading privileges upon which Scottish merchants had previously relied. Scottish overseas trading activity was further hampered by the Navigation Act, which cut Scottish ships out of international trade by forbidding the import of goods into England or her colonies unless carried in English ships or ships from the goods’ country of origin.

Beginning in 1651, the goal of the Act was to force colonial development into lines favourable to England, and stop direct colonial trade with the Netherlands, France, Scotland and Spain. This law was enacted despite the Union of Crowns, and effectively meant that Scots merchants were boycotted for trade in England and all her colonies. To make matters worse two powerful English trading companies – the East India Company and the Royal African Company – claimed monopolies on the rich trades with the East Indies and Africa and jealously guarded these territories.

This situation gave rise to the reasoning behind the Darien Scheme – access to trade. The architect of Darien was a man called William Paterson, who would the following year be instrumental in the foundation of the Bank of England. He devised a plan aimed at bringing financial prosperity to Scotland, proposing in 1693 that the Scottish Parliament should grant a Scottish monopoly on overseas trade to a trading company, enabling it to harness the lucrative and relatively available Far Eastern market in the same manner as the English had achieved with Africa and the Indies.

Key to the plan was the establishment of a Scottish colony in Central America, at a place called Darien (now part of Panama), so that goods could be transferred from the Pacific to the Atlantic without having to make the long and perilous journey around Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope. Instead, goods would be transported to the colony at Darien, on the Atlantic side of the Isthmus of Panama, and carried across to a port on the Pacific side, where ships with exchange cargoes from the East Indies and Asia would be waiting.

In 1695 the Bank Of Scotland was established and the Company Of Scotland was born, with its capital intended to be £600,000 raised by public subscription, of which half was to come from within Scotland and the rest from elsewhere. Investors in England, Amsterdam and Hamburg quickly raised their share, but the East India Company – fearing that their monopoly would be broken – used their influence on the king and English Parliament to persuade them to act against the venture.

The English government of King William III – anxious to be on good terms with Spain – didn’t need much persuading, as the proposed Scottish colony would be located on land the Spain had its own designs on. England was at war with France and hence didn’t want to offend the Spanish, who claimed the territory as part of New Granada. The East India Company threatened legal action on the grounds that the Scots had no authority from the king to raise funds outside the English realm, and obliged the promoters to refund subscriptions to the Hamburg investors, with English investors also quickly withdrawing their money.

This left no source of finance but Scotland itself, yet so fierce was the resentment at the duplicity of the king and English Parliament that Scots resolved to raise all the capital alone. Thousands of Scots put their own money into the enterprise alongside money from the nobles, and the Company raised just under £400,000 in a few weeks, with investments from every level of society and totalling roughly a fifth of the wealth of Scotland. This was an enormous sum for the time, amounting to about half the country’s available capital, despite it being a fully private venture.

Although the proposed location of the Company’s first colony was still a closely-guarded secret, preparations for the expedition were public and extensive. Ships, provisions and trading stock were bought in cities across Europe, crews were recruited and the expedition’s five ships assembled in the Firth of Forth.

The first fleet (Saint Andrew, Caledonia, Unicorn, Dolphin, and Endeavour) set sail from the east coast port of Leith so as to avoid observation by English warships, which they feared would capture or sink the traders. The plan was to make the journey around the north coast of Scotland, with the settlers below deck to hide the intent of the voyage. At a time when the total Scottish population amounted to only about one million, the amount of manpower committed to the venture was every bit as staggering as the financial commitment.

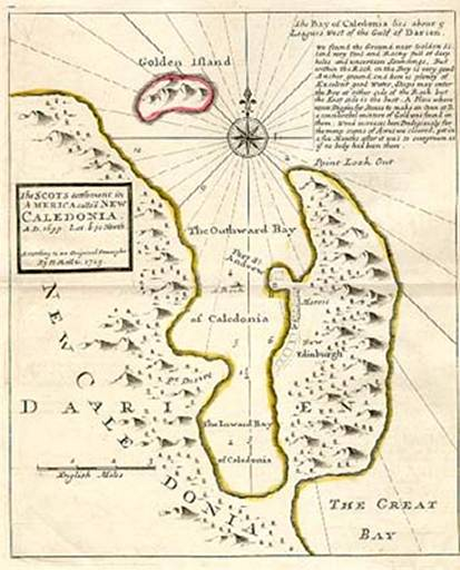

Even as they departed from Leith, the people on the expedition still didn’t know where they were going. It wasn’t until the ships had passed Madeira that the captains were allowed to open their sealed orders which revealed the ultimate destination. They were ‘to proceed to the Bay of Darien, and make the Isle called the Golden Island … some few leagues to the leeward of the mouth of the great River of Darien … and there make a settlement on the mainland’. The fleet made landfall off the coast of Darien on 2 November. The settlers christened their new home “New Caledonia”.

There they built Fort St Andrew and began to erect the huts of what they hoped would become their permanent town, New Edinburgh. They cleared land for farming, but successful agriculture proved difficult. The local indigenous people proved unwilling to buy the combs and other trinkets offered by the colonists, and no fleets of merchant ships arrived to use the trade route.

The lack of trade was not an accident, as the English colonies in the West Indies and North America had been forbidden to communicate with the Darien colonists or offer them any help or assistance, by order of William and his government in London. By the onset of summer the following year, the climate, disease and hunger had led to a large number of deaths in the colony. The settlement had intended that many of the settlers would be dispersed across the continent ferrying goods from coast to coast, not all holed up in one place. The confined living conditions combined with poor hygiene and little food led to an epidemic of dysentery. Eventually the mortality rate rose to ten settlers a day.

After eight months the colony was abandoned and the settlers began the journey back to Scotland. One ship, desperate for aid, arrived at the Jamaican city of Port Royal but was refused assistance in response to the king’s standing orders not to help the settlers. Dejected and betrayed by their own monarch, the settlers continued onwards with only 300 of the original 1,200 settlers returning on a single ship to Scotland. Those who managed to survive the journey and returned home found themselves regarded as a disgrace to their country, and even disowned by their families.

Back in Scotland, however, nobody knew that the colony had collapsed, and a second expedition with a further 1,300 settlers on board had set sail. The second expedition arrived at Darien to find the huts of New Edinburgh in disrepair and the jungle reclaiming the land, forcing the new settlers to rebuild the settlement. The persistence of the Scots prompted the Spanish to take measures to prevent the Scots from securing the land, despite the fact that the Spanish were not interested in settling the area themselves. Ships carrying supplies to the settlers failed to arrive and the ship carrying the settler’s food supply mysteriously caught fire and burned to ashes.

Hearing of Spanish intentions to complete the job with a direct attack, the exhausted and hungry Scots launched a pre-emptive strike on the Spanish fort. In retaliation the Spanish blockaded Fort St Andrew, with the Scots settlers bravely holding out for more than a month before eventually surrendering. Decimated by disease and hunger and defeated by the Spanish, the colonists left Darien for the last time in April 1700.

The failure of the scheme provoked tremendous discontent throughout lowland Scotland, where almost every family had been affected. Many held the English responsible, while believing that they could and should assist in yet another effort at making the scheme work. The company petitioned the king to affirm their right to the colony, but he declined, replying that although he was sorry the company had incurred such huge loses, to claim Darien would mean war with Spain. A prolonged, futile debate on the issue served to further increase bitterness.

After the failure of the Darien colony the Company of Scotland struggled on, attempting to establish trading links in Africa and the Far East. However, the capture of one of the company’s ships, the Annandale, at the instigation of the East India Company in 1704 led to an outbreak of Scottish anger towards England. Later that year the English ship Worcester was captured in a reprisal raid and its crew accused of being the pirates who had sunk another company ship, the Speedy Return, in 1703.

Although many in Scotland were delighted it soon became clear to the directors of the Darien Company that the charges were not supported by any solid proof, and it seemed that the men would be released. However, claims surfaced from the crew of the Worcester that the Captain had drunkenly boasted of taking the Speedy Return, killing the crew and burning the ship. The men were convicted and sentenced to death.

Queen Anne – who had succeeded William in 1702 – advised her 30 Privy Councillors in Edinburgh that the men should be pardoned, but the public demanded that the sentence be carried out. Nineteen of the Councillors made excuses to stay away from the deliberations on a reprieve, fearing the huge mob that had arrived in Edinburgh to demand that the sailors be put to death. The crew, who were clearly innocent, were duly hanged. Popular ballads of the time indicate that this was seen as direct revenge for the role of England in the failure of the Darien scheme.

For both William and Anne, the lessons of the Darien affair were clear. They were anxious to avoid war with Scotland, which was becoming increasingly likely, as this would result in the loss of their lands and associated rents. They also wanted to prevent the Scottish Parliament from granting conflicting trade privileges and interfering in England’s foreign policy by acting as a competitor. The result was the plan to undertake a union of the Scottish and English Parliaments.

And so the negotiations with the Scottish nobles began. With power concentrated in the hands of only a few men, the deal was far easier to swing, and a crucial part of the proposed Treaty was Article 14 – a direct bribe to the nobles. It granted £398,085 and 10s to Scotland, to offset future liability towards the English national debt. Scotland, it should be noted, had no national debt of its own at the time – the Darien Scheme having been entirely privately funded.

The payment of £398,000 (known as ‘the Equivalent’) was to be used to support Scottish industries and as compensation for Darien investors, but it ended up doing only one of those jobs – the latter. Some of the money was also used to hire spies, such as the author Daniel Defoe, whose first reports were of vivid descriptions of violent demonstrations against the Union.

“A Scots rabble is the worst of its kind… for every Scot in favour there is 99 against”

Sir George Lockhart, the only member of the Scottish negotiating team who opposed the Union, noted that “The whole nation appears against the Union” and Sir John Clerk, an ardent pro-unionist and Union negotiator, observed that the treaty was “contrary to the inclinations of at least three-fourths of the Kingdom”. Public opinion against the Treaty as it passed through the Scottish Parliament was voiced through petitions from shires, burghs, presbyteries and parishes. The Convention of Royal Burghs also petitioned against the Union and not one petition in favour of an incorporating union was received by Parliament.

On the day the treaty was signed, St Giles Cathedral rang its bells in the tune ‘Why should I be so sad on my wedding day?’ As the nobles signed the Act of Union of 1707 the Scots people rioted in the cities. The Act was signed in secrecy so as to avoid the mob baying for blood in the streets.

These were the events which Robert Burns would decades later bitterly sum up in the famous and oft-quoted lines “We’re bought and sold for English gold, sic a parcel of rogues in a nation”. Defoe would go on to document many more objections:

“Seeing, by the articles of Union, now under the consideration of the Honourable Estates of Parliament, it is agreed that Scotland and England shall be united into one kingdom; and that the united kingdoms be united by one and the same Parliament, by which our monarchy Is suppressed, our parliament extinguished, and in consequence our religion, church government, claim of right, laws, liberties, trade and all that is dear to us, daily in danger of being encroached upon, altered or wholly subverted by the English In a British Parliament, wherein the mean representation allowed for Scotland can never signify in securing to us the interest reserved by us, or granted to us by the English.”

The Treaty was nevertheless enshrined in law and ‘the Equivalent’ was released. The men appointed to distribute the compensation money were known as Commissioners of the Equivalent, and they set up in The Company of Scotland’s old offices in Milne Square, Edinburgh. Only part of the Equivalent had been paid in cash; the rest was issued to creditors in the form of debentures. Two societies of debenture-holders were formed – one in Edinburgh and one in London.

(Even more direct bribery was also said to be a factor, with a further £20,000 dispatched for distribution by the Earl of Glasgow with James Douglas, 2nd Duke of Queensberry, the Queen’s Commissioner in Parliament, receiving £12,325.)

In 1724 the two societies united to create the Equivalent Company. Three years later this company sought a royal charter to allow it to offer banking services outside its own membership. When the charter was granted, the new bank it created was called The Royal Bank of Scotland.

And so Darien brought about the Union, and the rest is history? But how does all of this play into the BritNat mythology we discussed back at the beginning? Well, ask yourself this: having read the events surrounding Darien, the subsequent neglect of Scotland by its own king and the malicious manoeuvrings of the English Government, would you consider the Union as an act of rescue from England towards Scotland?

It is, I’d venture, more akin to having your neighbour beat you with a baseball bat in order to gain access to your home, only to chastise you and claim you should be grateful for the first-aid they administered after they’d got your keys.

To describe the Union, as Professor Chalmers did this week, as a benefit that had “convinced the business classes that they needed the military protection of the Royal Navy if they were to benefit from the new riches that colonialism promised” is to stretch the truth to breaking point. In reality Scotland’s nobles were bullied and bribed into signing the treaty by their more powerful neighbour, and when they none-too-reluctantly acquiesced it wasn’t for the benefit of the people of Scotland.

Scotland was not bankrupt and could have continued on as an independent nation. But being in the Union benefited Scotland by removing the impact of the Navigation Acts (allowing the Scots to trade with the colonies) and removing the threat of English privateers commandeering or destroying Scottish shipping. Access to trade – the same goal pursued by the Darien Scheme – was what brought Scotland into union with England, not some mythological pride in “Britishness”.

The relevance of this knowledge today is not as a symbol of some fundamental national ineptitude or – as the Economist would have us believe – the inherent perils of independence. Rather, it’s a reminder that it was the simple mundane realities of trade, and trade alone, which originally bound us to the Union.

In today’s globalised free-market world, however, there are no English privateers roaming the North Sea, and we no longer require the permission of the monarchy to conduct international business. So why do we still need to be in the Union? And perhaps more to the point, what was it that the Economist was so scared of?

The failures of a private venture over 312 years ago have no bearing on the future prosperity of Scotland, however many time the Unionists drag them up. We are not bound by the mistakes of the past – we can learn, improve and adapt, as all nations must. Darien is not a monument to failure, but a testament to the ambition and drive that the Scots people can muster against overwhelming odds and adversity. Next time, though, the odds will not be so stacked against us.